The Brisbane Girls Grammar School Archive has unearthed some surprising and wonderful items. Often, they are immediately identifiable: a beautiful, old, silver badge with a bar and safety chain; or the 1925 Old Girls Dance Programme, with names filled in, and with a petite silver pencil still attached. One of my favourites is the handwritten program from an Old Girls Association dinner held in 1909 where the items on the menu are all listed as riddles. Try the soup clue, ‘The sixteenth letter’, or the vegetable dish—one that is ‘Bad for Ships’! However, at times, the origin and meaning of an item is much more obscure, as was the case of the photograph, ‘Aunt Grace’s House, “Arnwood” at Pine Rd, Mooroolbark, Vic(toria)’.

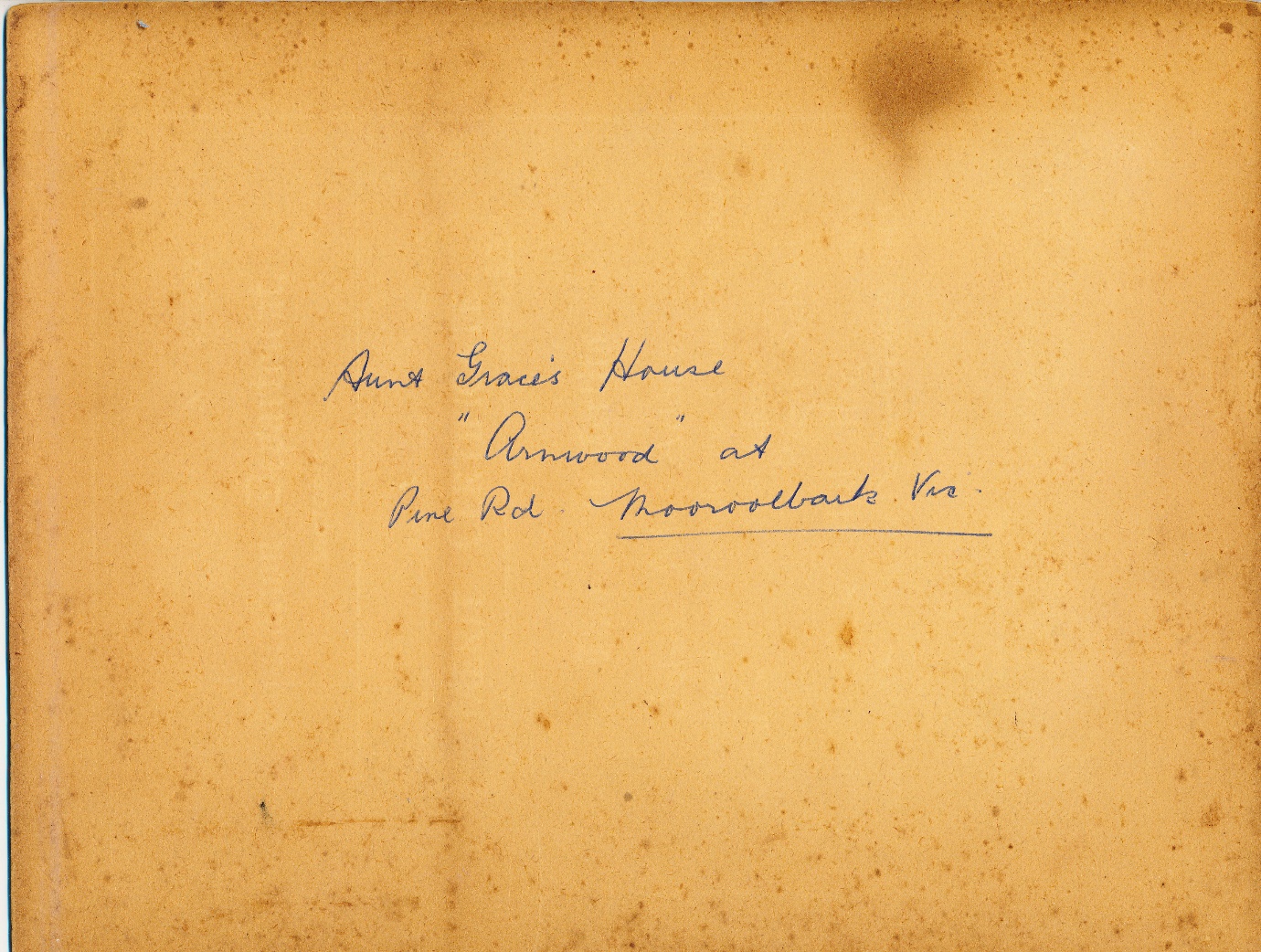

For a long time, an old 16 cm x 23 cm watercolour-enhanced photograph of a woman standing on the steps of a modest bungalow lay in a drawer overlooked and unidentified. The only clue to its identity were the words written on the back—’Arnwood’, ‘Mooroolbark’ and ‘Aunt Grace’s house’. Because of this lack of information, the photograph was pushed to the back of the drawer.

The reverse side of the 'Arnwood' photograph

Breakthroughs in archival research are often serendipitous and it was while I was searching through old Victorian newspapers that the name ‘Mooroolbark’ appeared in an article titled ‘Stretton water colours’. Miss Grace Margaret Wilson of Mooroolbark, a former Army Matron-in-Chief, was quoted as saying, with regards to a Stretton painting, ‘I wonder if it might have been done when Stretton was a war artist in France about 1916. He was living in No 3 AGH for a time, and, I know, did some water-colours. I have a view of the hospital he did for me’ (The Argus, 17 July 1948 p22). Imagine my delight when I read these few brief sentences!

Arthur Stretton’s scene of the third Australian General Hospital at Abbeville, near Amiens, Australian War Memorial collection

That leads us to Grace Margaret Wilson, who attended Girls Grammar in 1897 at the age of 17, having spent her primary school years at Brisbane Central State School. Her dedication to a long and amazing career is worth detailing.

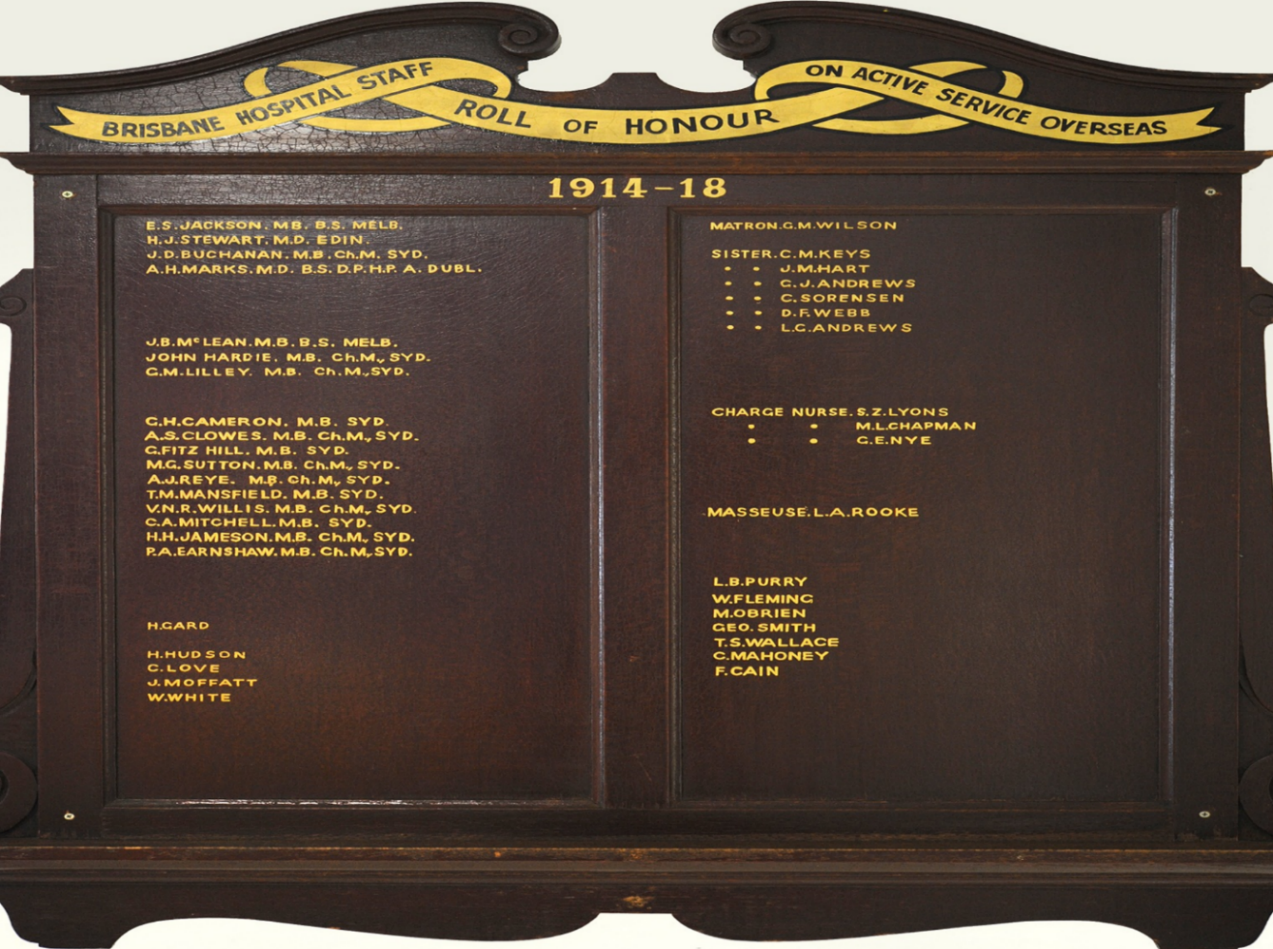

Six years after finishing her schooling, Grace undertook the three-year nursing training at Brisbane General Hospital, Herston, and, as the top graduating student, was awarded the first Gold Medal. This was the start of her long and illustrious nursing career. After graduating, Grace left for England where she continued to study and work, returning to Brisbane in 1914 to take up the position of matron of Brisbane Hospital.

Brisbane Hospital Honour Board WWI

When World War One (WWI) broke out, Grace volunteered for nursing duty and joined the Australian Army Nursing Service (AANS), following her brothers, Norman and Graeme, to the ‘Front’. From 1915 to 1919, most of her time was spent serving as matron of the Third Australian General Hospital, No 3 AGH, initially based on the island of Lemnos, where the hospital staff received and cared for the wounded soldiers from Gallipoli.

1915 Wilson and nurses arrive on Lemnos

An assessment of the Third Australian General Hospital and its nurses revealed a survival rate of 98.03 per cent (A G Butler, 1930). The Australian Director-General of Medical Services, Lieutenant General Featherstone, concluded in his report on the nurses on Lemnos, ‘I believe that the Hospital would have collapsed without the nurses. They all worked like demons and were led and guided by Miss Wilson’ (Jim Claven, September 2016). ‘Thousands of diggers and other Allied soldiers owed their lives to the care of Matron Grace Wilson and her nurses’ (Jim Claven, March 2016).

Brisbane Girls Grammar School alumnae, Kaye Vidgen’s (1961) grandfather, Major Herbert Jameson Stewart, was a medical officer at Lemnos at the same time as Grace, and Kaye recalled that her grandfather knew Grace well.

1916 Suez—Third Australian General Hospital staff with Grace Wilson (seated centre) and Major Stewart (seated on her right). Photograph by courtesy of Kaye Vidgen (1961)

Like many of the 2100 or more nurses who served during the war, Grace kept a diary and her accounts of the appalling conditions and waste of life reveal a strong independent woman, indignant and critical of the horrors endured by the men and women. When Grace passed through Alexandria in August 1915, her entry notes were that it was ‘a very French place, fascinating and pretty’, but it was here that Grace received news of the death of her brother, Graeme, killed by a sniper at Quinn’s Post, Gallipoli. She also had news that another brother, Norman, was safe and well in Heliopolis.

After the evacuation of Gallipoli in December 1915, the hospital moved to Egypt, and over the following years of the war, Grace was mentioned many times in despatches. She finally returned to Australia in 1920. She was awarded nursing’s highest honour in 1929, the Florence Nightingale Medal, for army nursing service and humane actions, and at the outbreak of World War Two in 1939 served as Matron-in-Chief of the Army Nursing Reserve. She was also posted for a short stint in the Middle East.

The Florence Nightingale medal is an international award presented to a nurse 'for exceptional courage and devotion to the wounded, sick or disabled'

1941 Matron-in-Chief of the Army Nursing Reserve, Grace Wilson

She initiated many developments in nursing during her career, focusing on the conditions, training, and wages available to nurses. Grace’s great-niece, Judy Campbell, recalled Grace visiting and caring for many of the nurses who had returned to Australia, but who were unable to reintegrate into their once-familiar lives. Grace was awarded the Royal Red Cross Medal, was made a Commander (Military) of the British Empire, and was the first woman to receive life membership of the Returned Servicemen’s League in 1953 (Daryl Passmore, 2013).

Grace retired from nursing in 1945 to live at Arnwood. She married Bruce Campbell at the age of 73. He, too, had joined the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and been involved in both World Wars. Grace died three years later in 1957.

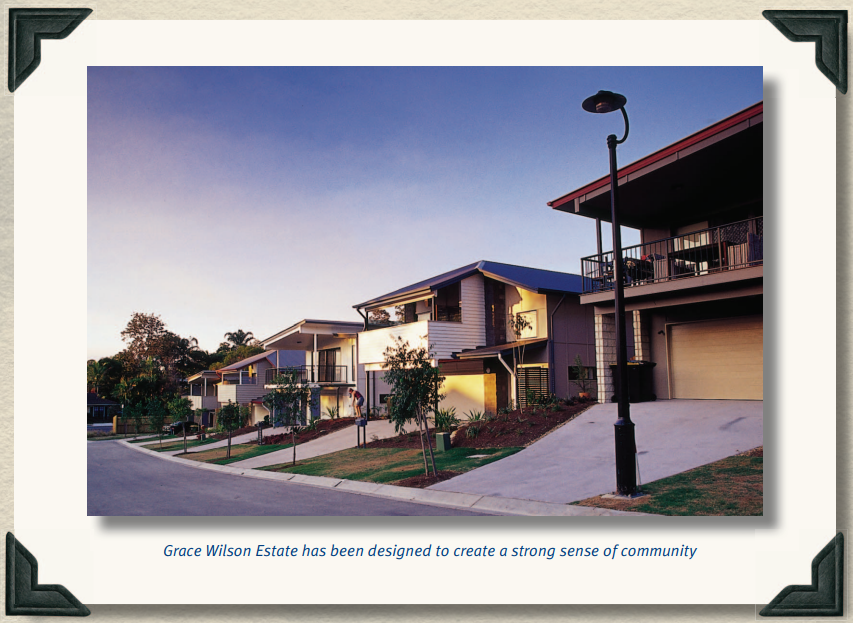

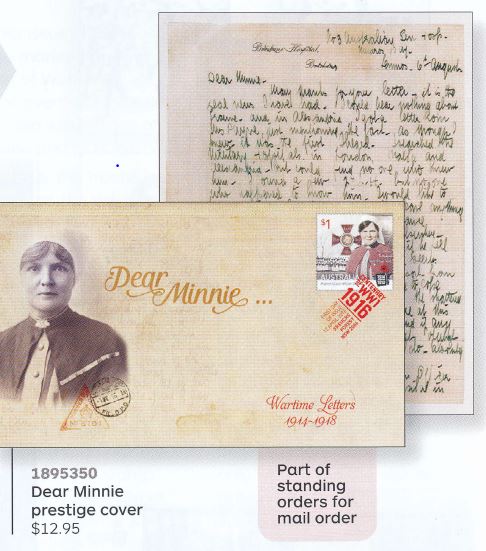

Grace’s devotion to her patients and fine work in both wars has been celebrated in small ways in her home state. Queensland Defence Housing named a housing estate for 50 ADF families after her, the Grace Wilson Estate in McDowell, and in 2015 she was recognised in a set of Queensland stamps created to commemorate the nurses of WWI on its 100th anniversary. Apart from these small gestures, she has been all but forgotten.

2016 Centenary of WWI: 1916 stamps

Recently, a small suburban house was put up for sale in Victoria. The property was described in the local paper as follows: ‘The first iconic English-styled cottage was built on just over half an acre and bears “Arnwood 1911” on the brass nameplate by the front door’. Another of Grace’s nieces, Margaret Shellshear, clearly remembered visiting her aunt while a young trainee nurse in Victoria in 1938. She was fortunate enough to spend the occasional weekend with her at Mooroolbark. Grace loved her garden and the minute they arrived home she would be on her hands and knees pulling out weeds or admiring bulbs that she had planted in her ‘scarlet oak grove’. No one today would guess that this charming, old cottage was once the home of one of Australia’s greatest war heroines.

‘Arnwood’ Mooroolbark—photograph is circa 1940

Mooroolbark in 2023

While the origins of our photograph remain a mystery, and Grace might be almost forgotten by the rest of Queensland, this once-overlooked item in the Girls Grammar Archive is a rare treasure. How did we acquire it? Was it through her relatives or family friend such as Kaye Vidgeon? Sadly, to date, all investigative avenues have been exhausted; we may never know. However, it is a timely reminder that even the most unassuming objects can represent a profound and significant history.

The photograph is a treasured memento of a Grammar girl who, at a time when women were grossly underestimated, made a difference. That image of the woman standing in front of a modest, but much-loved home and garden, reveals but a glimpse of her caring nature and belies the assured and dynamic nurse who faced and overcame the most parlous of circumstances for the benefit of others. What an inspiration she set for generations to come.

Mrs Jenny Davis

Sesquicentenary Research Officer

References

Andrews RRC, Sister Gertrude F ‘Experiences at the War’, The Australasian Nurses’ Journal. May 15, 1919, pgs. 162 – 166.

Bassett, Jan 1992 ‘Guns and Brooches’, OUP, Melbourne.

BGGS Strategic Design 2020-2022

Butler, Colonel A G. The Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, Part 1, Melbourne, Australian War Memorial, 1930. (A G Butler’s example in The Official History of the Australian Army Medical Services, p. 395 indicates that, up to 15 October 1915, only 77 out of 3906 cases admitted to the 3rd AGH died – a rate just less than 2 per cent).

Claven, Jim. March 2016 The lost photographs of Lemnos accessed on 25 October 2023. https://neoskosmos.com/en/2016/03/03/features/the-lost-photographs-of-lemnos/

Claven, Jim. ‘The Sister Evelyn Hutt World War I Collection: an Australian nurse at war’, La Trobe Journal, edition No. 98, September 2016.

Conversation with Judy Campbell and Researcher 30 October 2023.

Gill, B. ‘Notable Australian Women: Nursing has been her whole life’, Women’s Day and Home, June 1953, pg. 37.

Goodman, Rupert. 1985. Queensland nurses from Boer War to Vietnam pgs. 53, 55, Boolarong Publications.

House.speakingsame.com Property Description – http://house.speakingsame.com/p.php?q=Mooroolbark&sta=vic&id=564544

Passmore, Daryl ‘Heroic war nurse sadly forgotten’ The Sunday Mail 21 April 2013.

Shellshear, Margaret. Nursing Notes Vol 16 No 2 2009, Queensland members’ stories: Margaret Shellshear (Wilson 1941)

‘Stretton water colours.’ The Argus, 17 July 1948, p22.

Swain, Shurlee. ‘Wilson, Grace Margaret (1979-1957)’. The Encyclopedia of Leadership in twentieth-century Australia. Australian Catholic University. https://www.womenaustralia.info/leaders/biogs/WLE0535b.htm

Wilson, Sr Grace. ‘A transcript of the World War I Diary of Grace Wilson’, transcribed January 1989.

Whitmore, Mark Arthur Streeton and the art of war https://www.awm.gov.au/wartime/85/article-five. Accessed on 30 October 2023.

2013 Marjory Wilson, Grace’s niece, wearing Grace Wilson’s replica medals

2013 The Sunday Mail, 21.04.13 p26