While standing at the coffee counter in Tucker Up, I wonder if you notice the beautiful and unusual still-life photograph to the right. It asks the viewer to consider an intriguing array of beautiful silver, glass, metal, and bone household items, foodstuff, and, curiously, a beetle. Because of its food and drink content, it is appropriately positioned but does the casual observer know its purpose, history, and connection to the School?

9pm Elizabeth Bay House (2009) donated by the artist in 2009. Type C Print (from an edition of 5)

9pm Elizabeth Bay House (2009) in situ in the Barbara Fielding Room.

The photograph, by Grammar Woman, Robyn Stacey (1969), reflects the artist’s fascination with history, especially in what collections of objects from earlier times reveal to the modern viewer. This photograph is one of three the School is privileged to hold. All of these Type C prints: Leidenmaster (from ‘The Collector’s Nature’), Coral (from ‘Beau Monde’), and the one in question, 9pm Elizabeth Bay House (from ‘Empire Line’) interrogate idiosyncratic colonial lives and occupations at a time when ‘gentlemen’ had three points of interest: a library; a garden; and a collection.

Stacey is fascinated with artefacts and specimens, perhaps reflecting her subject choices of History and Zoology while at school. After a Fine Arts degree and developing an interest in photography, she began researching and photographing historical archive collections in Australia and overseas. Her sensitive and intriguing compilations draw on the tradition of Dutch still-life painting which has a long history in art.

9pm Elizabeth Bay House (2009) provides a sliver of insight into those who lived in this house in the nineteenth century. The house was built by Alexander Macleay, on land granted to him as the newly arrived Colonial Secretary. Apart from his government role, Macleay was a naturalist: an avid collector; identifier; and classifier. Stacey’s photographs capture not only the, at times, chaotic variety of the collection but also a glimpse of everyday life in the house.

Her still lives depicting items collected in earlier times, including the colonisation of Australia, are meant to be read as narratives of cultural heritage, as cultural stories. They reveal fascinating traces of life and habitation from Australia’s social history, and we can consider what they reveal in quiet moments in our busy lives.

Ms Lorraine Thornquist (1967)

Manager of Collections

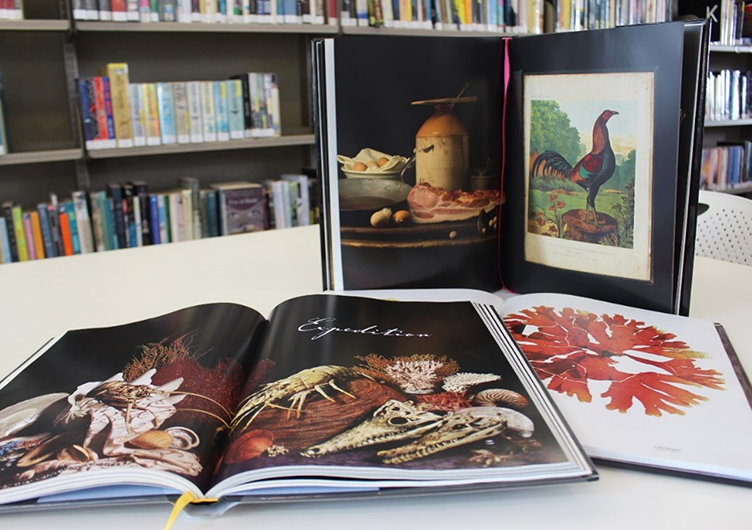

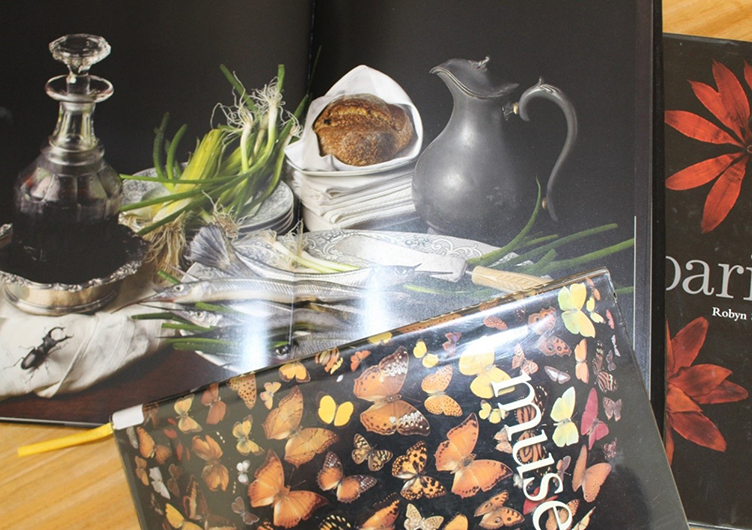

Books published by the artist and various authors, which are available in the School’s library.

Robyn Stacey publications: House, Museum and Herbarium

2008: Ms Robyn Stacey (1969) [second from right] with an OGA gift of her work to the School. She is shown here [left to right] with Mrs Christine Purvis (1965), Old Girls Association president, Principal, Dr Amanda Bell, and Ms Elizabeth Jameson AM (Head Girl, 1982), Chair of the Board of Trustees.

Robyn Stacey publications: House, Museum and Herbarium