It is that time of year when students wait for notification that their work has proven to be sufficient—or that they are about to discover they should have approached their assessment more strategically.

In earlier times, it was a dreaded envelope with the Grammar logo that arrived, addressed to the parents, that signalled either a special reward or a serious discussion. In this day of digital and continual reporting, the situation may be different, but I assume the feelings and reactions may be similar. This is one experience that holds true for generations of Grammar girls.

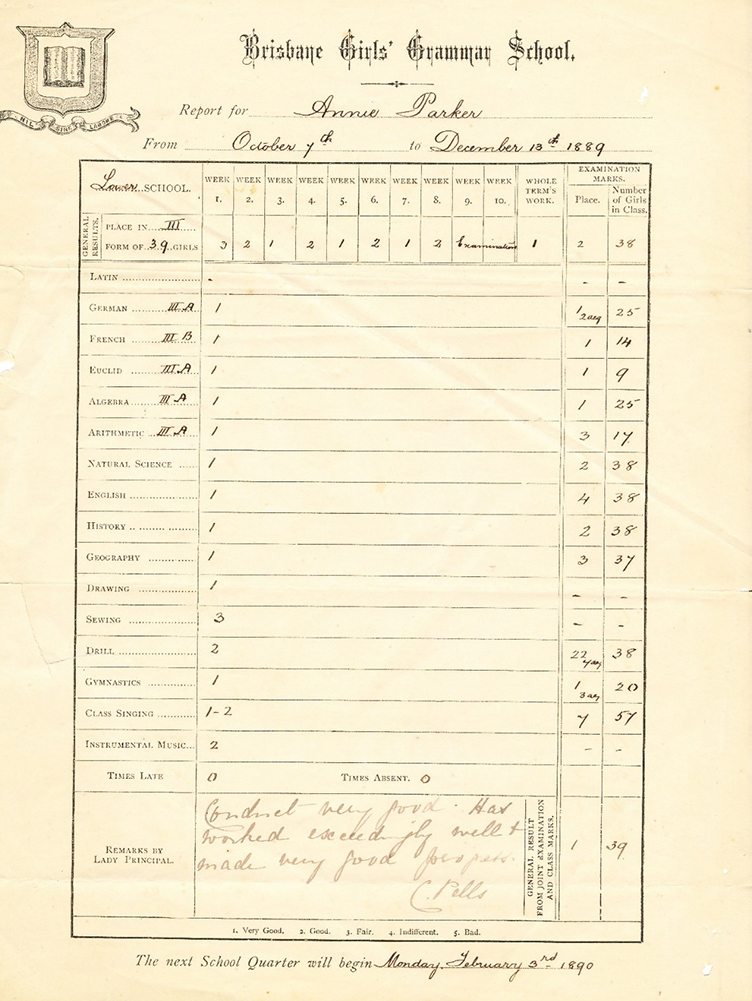

The School archive contains three reports for Harriett Hannah (Annie) Parker (1889-1893): two Lower School reports in 1889; and one in June 1893 for her performance in the Upper School. It is an interesting exercise to see how times have changed (or have not changed) this educational experience.

Annie Parker is the girl in the stylish outfit, front row, third from the right

Firstly, a close reader can glean interesting information from the earlier reports—there were 39 or 38 students in her Third Form, she was never late, nor did she miss one day of school, and the year was organised into four quarters. The comprehensive curriculum was also listed, and each girl received a result not only for all her academic subjects, but also for drawing, sewing, drill, gymnastics, class singing, and instrumental music. It is apparent that the School was developing that well-rounded Grammar girl from the very beginning.

Academic report for Annie Parker

One feature that might be unfamiliar to students after the 1950s is that the only comment made on Annie Parker’s reports was written by the Lady Principal, for every student, and in Miss Pells’ beautiful copperplate handwriting.

Fortunately for Annie, the comments were positive, but this was not always the case. The archive also holds a rather different third form (Year 9) report, dated December 1957. Unfortunately, the student—who we might call Molly—was not provided similar praise. Ms Alexis Macmillan, Acting Head Mistress, wrote that she had ‘not worked seriously this term and her progress has not been satisfactory. She must consider school work of primary importance and work very hard indeed next year if she wishes to recover the ground she has lost.’ No amount of elegant ink work would seem to alleviate the effect of such a pointed comment.

This 1957 report also displays the percentage gained by the student, the highest percentage gained by a student in the group, her place, and the number of girls in the class. This clear comparison to other students was part of reporting from the time of Annie Parker through to the 1960s. Indeed, when I attended Girls Grammar, at the end of every term throughout the year, the results for every subject examination taken by each student were prominently displayed for everyone to read in form rooms—and it was organised in order of merit. The public nature of this reporting was fine if your name was near the top but not so gratifying for students towards the other end.

The twenty-first-century reports are now digital and more private, with communication about each assessment piece sent out progressively as the evaluative procedures are completed. End-of-semester reports, interestingly, have a similar feel to the more austere nineteenth-century versions Annie Parker received. I wonder if, in one hundred years in the future, these modern versions will be accessed as easily and be as revealing as those lovely, yellowed, and treasured reports of Harriet (Annie) Parker.

Ms Kristine Cooke (Harvey 1967)

Director of the Library and Information Services

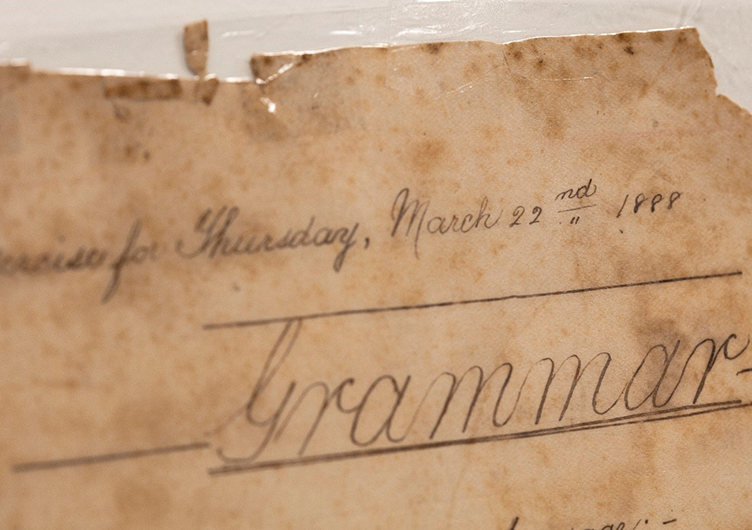

No wonder Annie Parker was awarded a ‘1. very good’ for drawing—even her classwork was artistic

1888 Annie Parker’s Exercise book

The sixty-two articles on Objects of Substance that have been published to date have often been accompanied by elegant and emotive photographic images. Many of these images are the creation of Ms Maxine McCabe, Technical Support AV Specialist, and I would like to thank her for her patience, creativity, and enthusiasm in the project.

Ms Pauline Harvey-Short, Manager, School History and Culture.