Susan Bleakley’s bronze, Ophelia, is a sculpture many of us walk past every day.

Situated at the bottom of the Grand Staircase in the Beanland Memorial Library, in the Elizabeth Jameson building, Ophelia kneels gracefully with her arms crossed over her chest and her feet overlapping. Her figure is unclothed, she casts her eyes down to the left, and her hair is tied up in a neat bun.

Susan Bleakley, Ophelia, 1999, bronze, Brisbane Girls Grammar School Collection

Susan Bleakley, Ophelia, 1999, bronze, Brisbane Girls Grammar School Collection

Truth be told, we already know a great deal about this doomed character from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Most significantly, we know Ophelia’s tragic ending. However, this sculpture is remarkably different from other renditions of her throughout art history. Importantly, she is nude and the upturned corners of her mouth belie the facts that we know about her—grief, madness, death.

One of the most famous artworks depicting the character of Ophelia is by the Pre-Raphaelite artist, John Everett Millais (1829-1896), now housed in the permanent collection of the Tate in London. Painted between 1851 and 1852, it is a truly captivating mixture of melancholy and beauty, hopelessness, and nature, but ultimately, it is a tragedy that radiates from the canvas. The juxtaposition of the delicate flowers, lush foliage, vivid colour, and extreme detail of the landscape against the figure of the woman drowning is striking, and it is this very characteristic that made it such a revolutionary picture in its time.

John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1851-2, oil on canvas, Tate, London

Susan Bleakley sculpted our Ophelia in 1999, having previously painted the portrait of Judith Hancock in 1993. It was to be the Year 12 cohort’s gift to the School. Bleakley was born in Brisbane in 1948 and studied Art at the Brisbane Technical College (now the Queensland University of Technology). She received mentorship in sculpture from the award-winning artist, Mark Lee Bernstein, as well as Frank Lambert.

Bleakley generously shared her Grammar Ophelia story with me. She was initially contacted by Head Girls, Sally Brand (1999) and Judy Hainsworth (1999). From photographs of her work, Ophelia was quickly selected. The piece was originally sculpted in clay and, subsequently, moulds were made from silicone and then plaster. Next, the sculpture was cast in wax, and later revised using heated apparatus.

A local foundry in Brisbane, Perides Art Foundry, cast the sculpture in bronze utilising the ‘lost-wax’ process which involves the wax being heated away by the molten metal—an uncommon technique in Australia. Once the bronze is finished, various chemicals are then applied to produce the patina or oxidisation. These processes can be natural or contrived, and are ‘used to accentuate pieces, provide contrast, imply age, introduce colour to the bronze, and sometimes to add a dose of reality’ (randolphrose blog, accessed 2023). Only six editions of Ophelia were cast.

Sally, who now works in the arts, revealed that this sculptural commission was one of her first forays into the creative field. Judy recalled Sally recommending Bleakley as the artist they should contact, and together they received advice from Sally’s mother, who worked at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. Judy admitted that her interest in theatre influenced her being drawn to a sculpture titled Ophelia. Judy remembered: ‘Kenneth Branagh’s film adaptation (of Hamlet) had been released a few years earlier in 1996 and I remember going to see the four-hour director’s cut at the Regent Theatre in the city. I was a big fan’ (Hainsworth 16.10.23).

Bleakley’s Ophelia is clearly an adolescent approaching womanhood. She coyly shields her body, and her torso is twisted in line with her gaze. Her hair, incidentally, is neatly drawn up, contrary to other portrayals of her—those long, wild tendrils traditionally symbolic of Ophelia’s lost mind. Bleakley made the conscious decision to portray Ophelia nude: ‘I chose to sculpt her unclothed to best represent the line and form of the human body’ (Bleakley 20.9.2023). Thus, the artist found the subject more artistically interesting to sculpt her body this way. Indeed, the character’s figure speaks volumes; Ophelia kneels as if in reverence and her limbs overlap in self-preservation. Certainly, as a visual device, the young woman’s crossed arms operate to lead the eye directly to her face.

Susan Bleakley, Ophelia (detail), 1999, bronze, Brisbane Girls Grammar School Collection

Susan Bleakley, Ophelia, 1999, bronze, Brisbane Girls Grammar School Collection

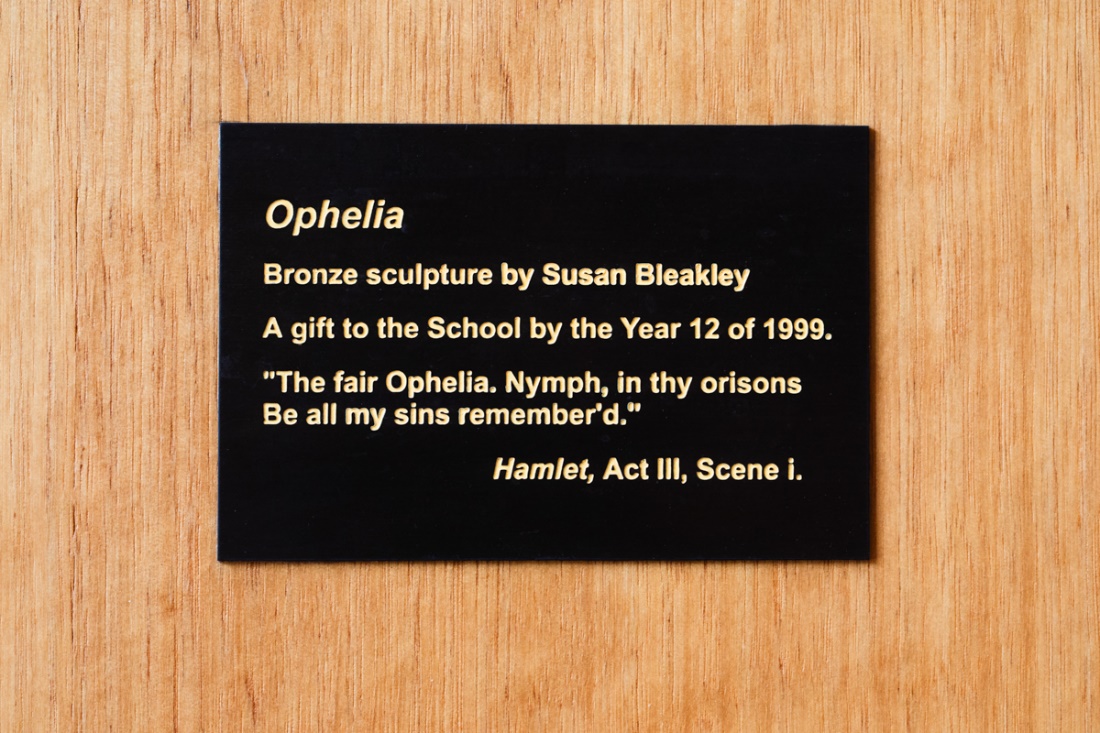

Bleakley’s sculpture rests on a wooden plinth, upon which a plaque includes the Hamlet quotation: ‘The fair Ophelia. Nymph, in thy orisons/Be all my sins remember’d. [Hamlet, Act III, Scene i].’

Susan Bleakley, Ophelia Plaque, 1999

So, Bleakley had a specific scene of the play in mind when creating her artwork. In this scene, after an exchange of pleasantries, Ophelia announces that she has ‘love-tokens’ of Hamlet’s that she wishes to return to him. He flatly denies he gave her anything. Ophelia maintains her composure and stands firm.

In the ensuing exchange between Ophelia and Hamlet, Ophelia is not meek or tame; she has a strong voice. This passage highlights that it is Hamlet who is flawed—his lies are petulant, and Ophelia’s resolve and honesty are obvious, both character traits that this gift celebrates.

The tradition of giving has a rich history at Girls Grammar, from donors such as the Old Girls Association, to the Parents & Friends, and of course, the graduating Year 12 classes, as well as many more groups and individuals.

Artworks, furniture, practical items—such as clocks and banners—and Speech Day prizes have been gifted, along with perhaps more important gifts of time and talent of Grammar Women, and parents and friends of the School.

The intentions behind the generosity of giving are to develop the art and object collection, construct new, and extend existing buildings, to improve the campus, and to bestow prizes for students to seek further opportunities in specific subject areas. What continues after the act of giving is the legacy that is left behind when we leave Girls Grammar.

Perhaps the 1999 gift inspired the selection of Hamlet as the 2003 joint production between Brisbane Grammar School and Brisbane Girls Grammar School, directed by Michael Beh. Of the 25 cast members, Francesca (Frankey) Bianchi (2004) played Ophelia, before beginning her career as an actor and on-set dialect coach in Canada. Frankey recently shared her experience of acting in Hamlet nearly two decades ago: ‘It was my first real exploration of Shakespeare. We sat at desks and read his work in class but that doesn’t compare to the visceral exploration I was gifted with onstage in that show. I’m a professional actor now so I know my work was probably awful! But that show planted the seed for me and marked the beginning of my love for that text and being on stage’ (Bianchi 28.10.2023).

Brisbane Grammar School and Brisbane Girls Grammar School Senior Play Program, Hamlet, 2003

Brisbane Grammar School and Brisbane Girls Grammar School Senior Play, Hamlet, 2003. Frankey Bianchi bottom left

As with Frankey’s portrayal of Ophelia, Bleakley effectively captured Ophelia’s innocence and vulnerability but, at the same time, conveyed her unwillingness to yield. Although, she first appears to be subjugated and defeated, some see a quiet strength and loyalty. This dichotomous quality would be most familiar to generations of Year 12 Grammar girls who studied the play, and perhaps especially the 2023 cohort who, only last week, wrote their external exam on Hamlet.

Susan Bleakley, Ophelia (detail), 1999, bronze, Brisbane Girls Grammar School Collection

Ophelia has traversed the boundaries of play, theatre, film, reimagined storytelling, music, and art. In Bleakley’s sculpture, Ophelia is forever young. As she shields her body from the viewer’s voyeuristic gaze, there is a strength about her. In her speech to Hamlet, she defends herself. As one of the two female characters in the play, her story has taken on a life of its own. Bleakley chose to empower her sculpture in the same way, focusing on her beauty—the form and line of her body. Her quietude, faith, and above all, resilience is inspiring. This rare vision of Ophelia is timeless.

Dr Dominique Baines

Archivist

References

Rylands, George (ed.). New Clarendon Shakespeare: Hamlet, Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1982, pp. 112-115, 167-169.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/millais-ophelia-n01506

Accessed: 15 September, 2023

https://www.susanbleakleysculptor.com/about-susan-bleakley/

Accessed: 15 September, 2023

https://randolphrose.com/blogs/blog/what-is-patina-and-how-it-is-used-with-bronze-sculptures

Accessed: 22 September, 2023

https://www.thecollector.com/shakespeares-ophelia-art/#The%20Nude%20Ophelia

Accessed: 18 September, 2023

https://www.bl.uk/shakespeare/articles/ophelia-gender-and-madness

Accessed: 18 September, 2023

https://myshakespeare.com/hamlet/act-3-scene-1

Accessed: 19 September, 2023

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sarah-Bernhardt

Accessed: 22 September, 2023

https://nmwa.org/art/artists/sarah-bernhardt/

Accessed: 22 September, 2023

https://www.huffpost.com/entry/nude-photos-ophelia_n_575f069fe4b053d43305d07b

Accessed: 25 September, 2023

https://www.nga.gov/collection/highlights/degas-little-dancer-aged-fourteen.html

Accessed: 29 September, 2023

Accessed: 29 September, 2023

Brisbane Girls Grammar School Magazine, 2003, p. 150.

Brisbane Girls Grammar School Grammar Gazette, Winter 2003, p. 10.

Brisbane Grammar School and Brisbane Girls Grammar School Senior Play Program, Hamlet, 2003.

Peterson, Kaara, “Framing Ophelia: Representation and the Pictorial Tradition” in Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal, Vol. 31, No. 3, September: 1998, pp. 1-24.

Email correspondence with Susan Bleakley, 20 September, 2023.

Email correspondence between Dominique Baines and Pauline Harvey-Short, 4 October 2023.

Email correspondence between Dominique Baines and Sally Brand, 5 October, 2023.

Email correspondence between Dominique Baines and Judy Hainsworth, 16 October, 2023.

Message exchange between Dominique Baines and Francesca Bianchi, 28 October, 2023.

https://www.themoviedb.org/person/1669343-francesca-bianchi

Accessed: 17 October, 2023

https://randolphrose.com/blogs/blog/what-is-patina-and-how-it-is-used-with-bronze-sculptures

Accessed: 22 September, 2023