2023 was a splendid year of discovery for Objects of Substance. Not only did staff uncover a school safe from the turn of the previous century, but we also learned of a corporate seal, which appears to predate it.

The Brisbane Girls Grammar School Corporate Seal, c. 1884

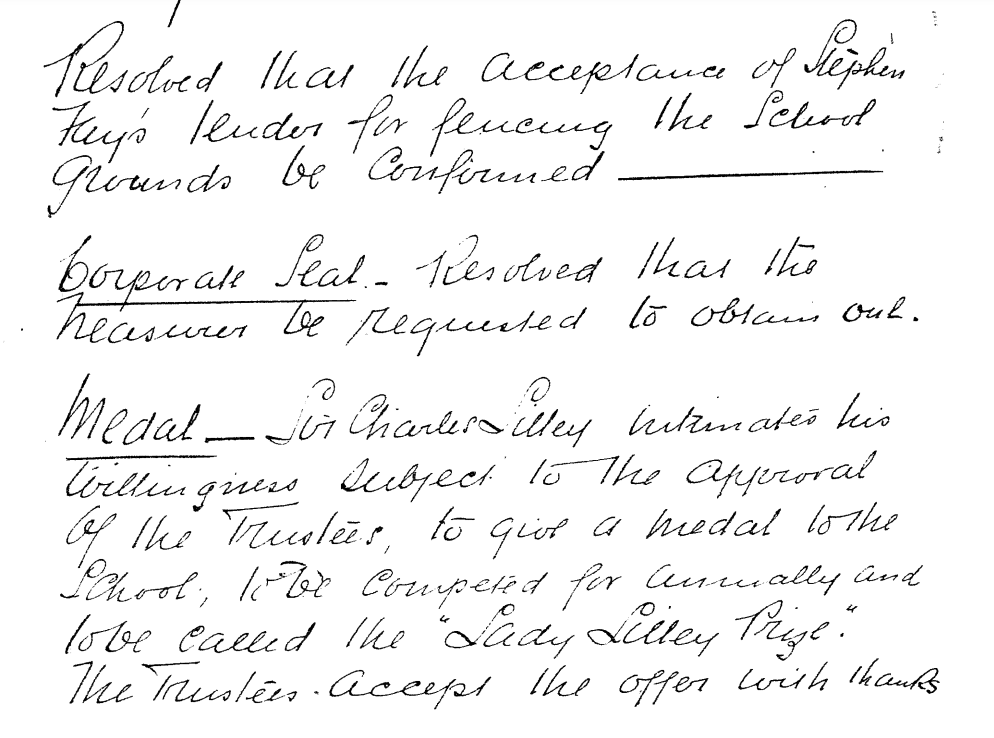

Deep in the Board Minutes of 31 March 1884, in the presence of the Chief Justice of Queensland and Former Premier of Queensland, Mr Charles Lilley, Sir Samuel Walker Griffith, and Lady Principal, Ms Sophia Beanland, it was recorded: ‘Corporate Seal—Resolved that the Treasurer be requested to obtain one’. We can only assume that the seal we now possess was designed, manufactured, and purchased as a direct result of the intention declared during this meeting.

Brisbane Girls Grammar School Board Minutes, 31 March 1884, p 37

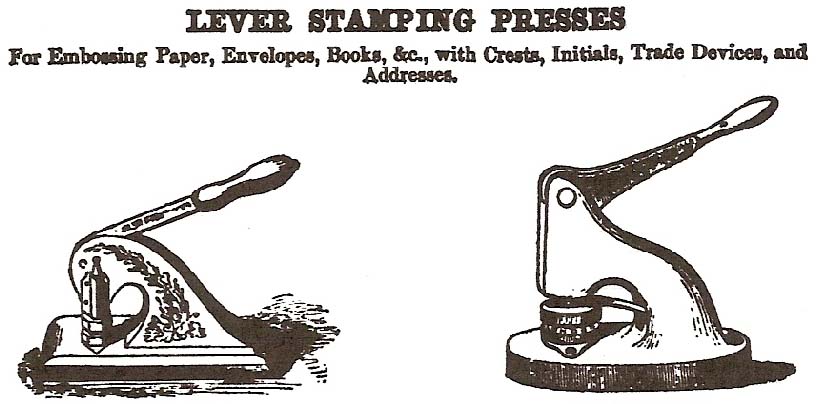

The Brisbane Girls Grammar School seal employs a lever press mechanism that allows the user to produce a crisply embossed coat of arms. Incredibly, the seal is still utilised by the School Board today for the marking of official documents. But it is more than a visible indentation on paper that makes this administrative item so significant—for the act itself signifies a legal agreement and culminates in a highly symbolic gesture that harks back hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

The Brisbane Girls Grammar School Corporate Seal and Wooden Box (detail), c. 1884

Affixing the seal represents the formal deed of a corporate body and therefore it is bound-up in honour. The pressing of the paper ensures authenticity and denotes authority. Technically, this practice is not legally required today, however, organisations may still choose to mark papers in this manner. This relatively simple act reflects who we are, what we represent, and how we wish to be recognised. Coming together as a unified body and continuing traditions matter to us.

Immediate past Chair of the Board of Trustees, Elizabeth Jameson (Head Girl, 1982) commented on the seal: ‘Oh yes, we used it alright. Rachel Fraser (1988), former Chief Financial Officer, and I used to admire this extraordinary object. We used it in my time … I feel mainly when we did things like bought Bread House … It is magnificent … I’m not sure if any of the other grammar schools still have theirs … In fact, in 30 years and squillions of boards, I never came across another organisation who had one, yet they all must have at one time’ (4.12.2023).

Lever Stamping Presses, Exhibited 1855 (Paris), Waterlow & Sons, London

The School Seal Policy, Section 3 (b), clearly states that ‘The seal may only be affixed:

- to Relevant Documents in pursuance of a resolution of the Board;

- by the Secretary to the Board, in the presence of the Chair.’

In addition, a register is kept recording the use of the seal and the documents to which it is affixed.

The branch of study that deals with ‘wax, lead, clay, and other seals used to authenticate archival documents’ is known as sigillography or, from the Greek, sphragistics. The tradition of marking written communication with impressions—particularly with wax—became a popular Western convention throughout the tenth century; the primary aim being authentication.

To paraphrase author, Hilary Jenkinson, it was during the Medieval Era that the act of writing was carried out by professionals, namely clerks; royalty and aristocracy did not do it themselves. The rate of illiteracy was high; therefore, seals came in very useful. Conversely, as the rate of reading and writing increased centuries later, the utilisation of seals thus declined.

The corporate seal is currently located in Personal Assistant to the Board Secretary, Ms Kirsti Moyle’s (1992) office in the Main Building, which coincidently was completed the same year as the seal: 1884. As was the contemporary practice, the seal was carefully hand-painted with exquisite gold leaves, dainty red flowers and matching red buds. However, some seal presses were so ornate that they were integrated with the heads of lions or eagles. Others, known as percussion presses (similar to how staplers work today) had frogs or buffalos worked into their composition, but my personal favourite is that of the lever seal press exhibiting a human hand in its overall design.

Left and Right-Hand American Seal Presses, c. 1860s

Although it does not appear as such, our seal is heavy. Seal presses can average a weight of ten pounds, which is the equivalent to more than four and a half kilograms. But contrary to its weighty might, the seal was obviously designed for portability. It is housed in a custom-made wooden box that can be locked with a key, complete with a metal handle for ease and comfort during transportation.

The Brisbane Girls Grammar School Corporate Seal and Wooden Box, c. 1884

The imprinted image of the seal itself is quite simple. It features the School Crest in the centre, and below that, the Latin motto ‘Nil Sine Labore’, which is encircled by a border containing the words ‘The Brisbane Girls Grammar School’, topped off with ‘The Board of Trustees’. The consistent shape of the matrix, or die, as it is known, being a circle, was deliberate as it represented the lowest risk of damage.

The Brisbane Girls Grammar School Corporate Seal Matrix, c. 1884

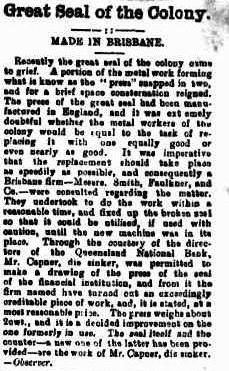

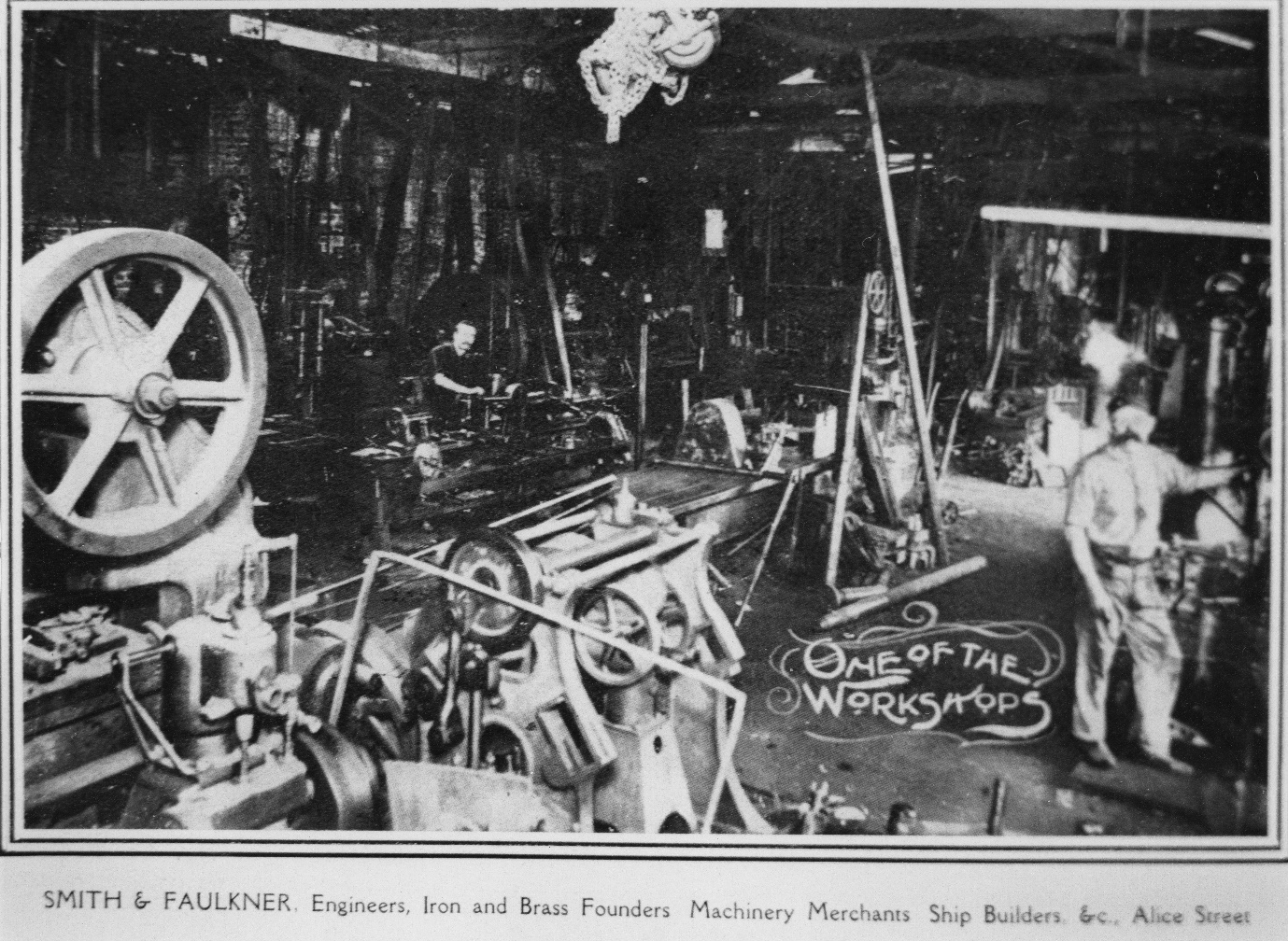

Surprisingly, however, the seal is unmarked, which is where our trail of provenance ends, and only speculation can begin. There were undoubtedly manufacturers in Brisbane who could have forged this seal at the time. Take for instance, the foundry in Alice Street which crafted the ‘Great Seal for the Colony’ throughout 1894. The company of Smith & Faulkner took on the rather daunting task of repairing the Great Seal, which was originally made in England. As the below article attests, the seal was in bad shape, having ‘snapped in two’, and it was dubious as to whether there would be a local foundry fit for the job. Nevertheless, Smith & Faulkner proved their worth in the production of ‘an exceedingly creditable piece of work … at a most reasonable price … and it is a decided improvement on the one formerly in use’.

The Queensland Times, Saturday April 7 1894, p 5

Yard of Smith & Faulkner, Alice Street, Brisbane, c. 1909. Image: State Library of Queensland

It is with great joy that historians unearth and subsequently learn from objects like these—ones that we can physically touch, tangible pieces of history. To make an item like this visible to our community is meaningful for many reasons. The quality workmanship, decorative elements, its longstanding use, and traditional practice highlight that even humble, functional objects can be thoughtfully manufactured and delicately hand-painted. This careful consideration for our everyday conventions is something we should replicate today, in many things, for these are the important lessons we can learn from the past.

Dr Dominique Baines

Archivist

Interior of Smith & Faulkner Workshop, Alice Street, Brisbane, c. 1909. Image: State Library of Queensland

References

Brisbane Girls Grammar School Board Minutes, 31st March, 1884, p 37.

https://www.officemuseum.com/seal_presses.htm

Accessed: 23 November 2023

Email correspondence between Kirsti Moyle and Dominique Baines, 30 November, 2023.

Email correspondence between Pauline Harvey-Short and Elizabeth Jameson, 4 December 2023.

Board of Trustees, Brisbane Girls Grammar School Seal Policy, June 2023.

Jenkinson, Hilary, The Great Seal of England, ‘Journal of the Royal Society of Arts’, Vol 101, No 4902, Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce: 1953, pp 550-563.

‘Great Seal of the Colony’, The Queensland Times, Saturday April 7 1894, p 5.

http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article123751384

Accessed: 23 November 2023